To create a more just society, African Americans embraced nonviolence to dismantle racial segregation during the Modern Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. Today, a series of 13 iconic places along the U.S. Civil Rights Trail are being nominated for recognition as World Heritage Sites.

World Heritage aims to identify, protect, and preserve cultural and natural properties around the globe that manifest Outstanding Universal Value for all humanity. Considered the most successful international treaty ever ratified having been proposed by the United States in 1972 and approved by every nation, the World Heritage Convention authorizes a committee of 21 signatories to oversee the work identifying and monitoring these heritage sites so that they will last in perpetuity.

1Property meets one or more of 10 World Heritage criteria

2Property meets conditions of integrity and authenticity

3Property meets requirements for protection and management

The World Heritage List includes 1,199 properties located in 168 countries, with Italy and China having the most sites inscribed.

The United States has 25 properties inscribed on the World Heritage List, with half being cultural sites and the other half natural sites.

Nominated under Criterion (vi), the United States Civil Rights Movement Sites represent events of global significance at which nonviolence removed racial segregation in the built environment and advanced racial equality. When considered with colonial independence in India and the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, the American movement joined in the 20th century’s global challenge to white supremacy to achieve racial integration and equality. Today, these 13 heritage sites interpret the past while promoting racial reconciliation through ongoing programs designed to create “a more perfect union.”

Civil rights veterans joined stakeholders in proposing several movement sites to the U.S. Tentative List for World Heritage in 2008 with the goal of adding additional properties that would represent the overall nonviolent struggle for racial change in modern America. The Georgia State University World Heritage Initiative formed in 2016 to fulfill that objective, working with more than 75 scholars and dozens of local, state, and federal historic preservationists, and global authorities on world heritage in preparing the Serial Nomination’s draft dossier.

In 2023, the World Heritage Centre authorized the International Council on Monuments and Sites to conduct an “upstream review” of the dossier, which included an Advisory Mission to 10 of the proposed sites in six states over seven days. The resulting assessment provided a blueprint for preparing the final dossier.

The Modern Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s occurred in the United States South where the legacy of African slavery had evolved into a system of legal white supremacy maintained by racial segregation and other discriminatory laws. Once the plantation system of coerced labor collapsed during the Great Depression and new opportunities in manufacturing materialized with World War II, African Americans demanded equal access to the new consumer society that emerged in the postwar era.

The map highlights the globally significant civil rights events of the modern era, all of which occurred in the South where African Americans challenged racial segregation in order to remove barriers and gain equal access. Lawsuits filed in Kansas and Virginia joined others in becoming the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education challenge over racially separate and unequal schools, resulting in the U.S. Supreme Court’s desegregation ruling enforced in Arkansas. Demonstrations over whites-only facilities in North Carolina, Georgia, Alabama and Mississippi expanded the desegregation ruling to public accommodations. Demands for change in Washington, D.C., and Tennessee expanded the race reforms.

Led by 16-year-old Barbara Johns, the African American student strike at Robert Russa Moton High School in 1951 resulted in a lawsuit that joined four others in the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown decision on school desegregation in 1954. Despite the intransigence of white officials with their strategy of massive resistance to thwart the ruling, the Black student protest ultimately resulted in the integration of Prince Edward County public schools.

Address

900 Griffin Boulevard, Farmville, VA, United States

African American families filed a lawsuit challenging the idea of separate but equal educational facilities, headlining the five cases that the U.S. Supreme Court combined as Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas in its desegregation ruling. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People had filed similar challenges in Virginia, South Carolina, Delaware and Washington, D.C., and it successfully argued its case before the high court that racial separation in education was inherently unequal.

Address

1515 Southeast Monroe Street, Topeka, KS, United States

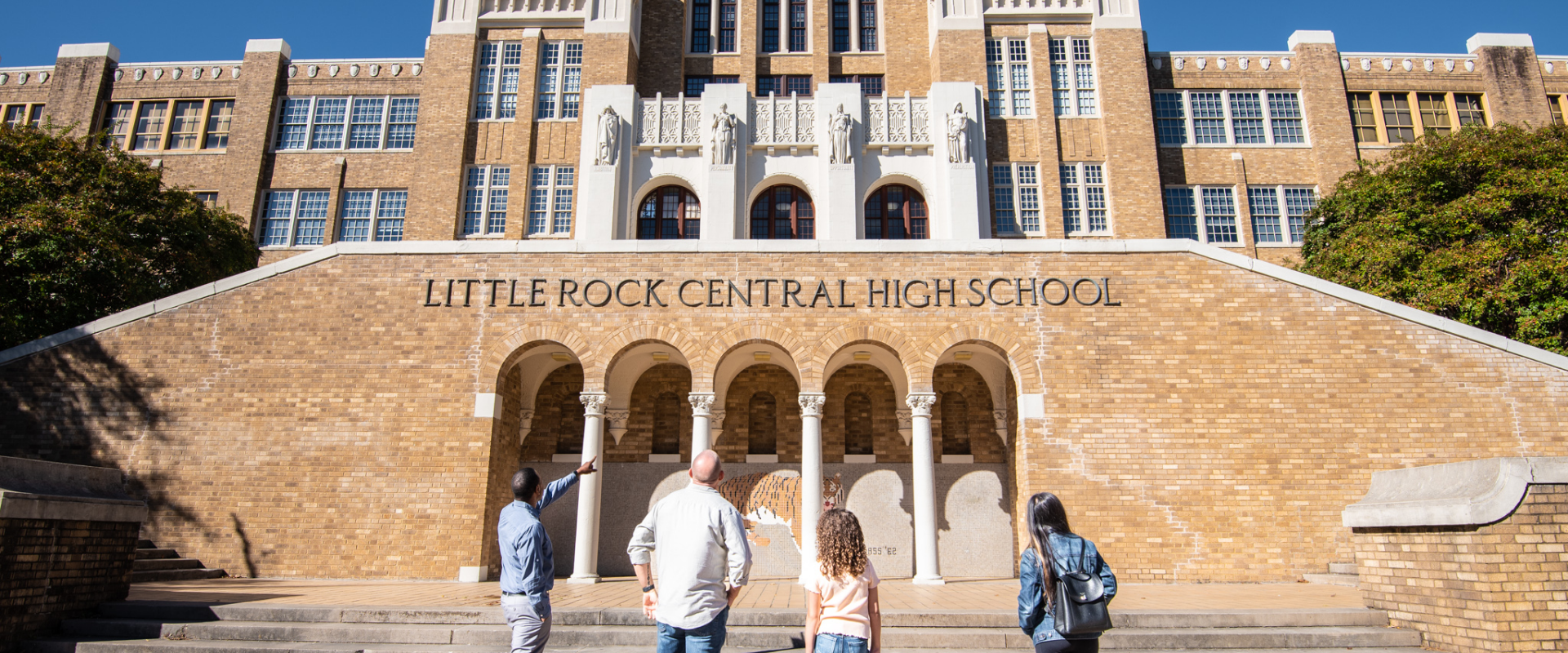

Filing a lawsuit to desegregate Little Rock’s schools in accordance with the Brown decision, Daisy Bates of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People assisted the nine African American students who registered at whites-only Central High School in 1957. When a white mob formed to prevent the Black students from entering the school, Gov. Orval Faubus ordered the Arkansas National Guard to block their admission in a defense of the white supremacist strategy of massive resistance. Rebuking the challenge to federal authority, President Dwight D. Eisenhower nationalized the guard and sent in the 101st Airborne Division to escort the Little Rock Nine to class.

Address

1500 South Park Street, Little Rock, AR, United States

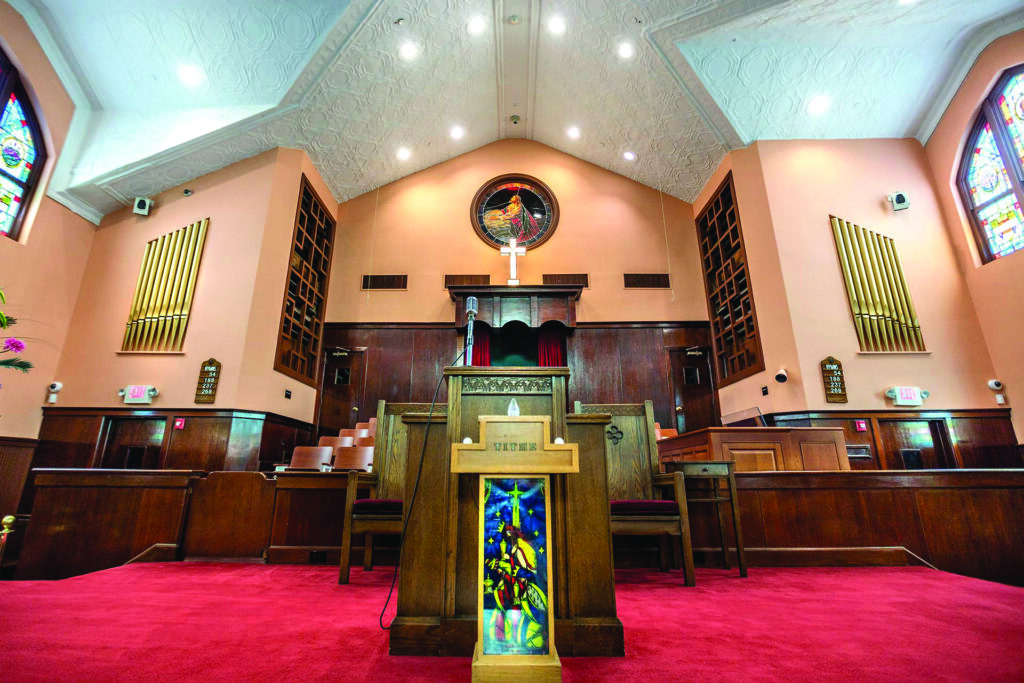

When police arrested civil rights activist Rosa Parks over segregated seating on public transportation, African Americans in Montgomery organized in protest. One hundred Black leaders gathered in Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, where its new pastor, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., supported church member Jo Ann Robinson of the Women’s Political Council and its plan for a boycott of the buses. At the night’s mass meeting, those in attendance elected Dr. King to head the newly organized Montgomery Improvement Association, which would coordinate the yearlong protest that brought Dr. King to international fame and resulted in the application of the Brown decision against all forms of racial segregation.

Address

454 Dexter Avenue, Montgomery, AL 36104

Growing up in Atlanta’s Black business district along Auburn Avenue, where generations of his family pastored Ebenezer Baptist Church, and educated at nearby Morehouse College, whose president Benjamin Mays had met Gandhi as had famous alumnus and theologian Howard Thurman, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. emerged out of the goals and aspirations of African Americans and expressed a new Black theology that embraced nonviolence. Building on the successful Montgomery Bus Boycott, Dr. King joined other Black ministers in organizing at Ebenezer the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), which headquartered on Auburn Avenue with Dr. King as president while also serving as co-pastor at Ebenezer.

Address

407 Auburn Avenue Northeast, Atlanta, GA 30312, United States

From the pulpit of Bethel Baptist Church, the Rev. Fred L. Shuttlesworth joined Dr. King and other charismatic leaders in fighting to dismantle racial segregation. When the courts ordered Montgomery to desegregate buses in 1956, Shuttlesworth announced a challenge to Birmingham’s buses, only to have his home bombed. His survival of the blast convinced others of his determination, and his repeated challenges to white supremacy and the violent suppression he suffered did not deter his followers. The protests culminating in the 1963 civil rights campaign, despite fire hoses and police dogs, resulted in federal support for race reform.

Address

3233 29th Avenue North, Birmingham, AL 35207, USA

When four Black men sat down at the whites-only lunch counter in the Greensboro, North Carolina, F. W. Woolworth Company building, their act of civil disobedience shifted movement strategy away from a reliance on boycotts and lawsuits to nonviolent direct action. Matriculating at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical College, the NC A&T Four attracted the attention of other students who spread the protest across the state, then region, as 70,000 people participated in sit-ins over the next six months. Already in Nashville, former missionary to India and Gandhi disciple James Lawson had trained a cadre of students in nonviolence, and they helped others organize the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee to coordinate the youthful demonstrations.

Address

134 South Elm Street, Greensboro, NC, United States

Congress of Racial Equality co-founder James Farmer reprised the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation as the 1961 Freedom Rides to test the desegregation by court ruling of facilities engaged in interstate transportation. Black and white integrationists boarded Greyhound and Trailways buses in Washington, D.C., headed to New Orleans, intending for nonviolent challenges to separate public accommodations whenever they found them still in use. When the integrationists reached Anniston, Alabama, the Trailways bus managed to avoid a white mob forming to stop the protest, but when the Greyhound bus reached its depot, the mob attacked the vehicle, refusing any to disembark and puncturing the tires. They chased the bus 6 miles from town and once the tires went flat forced it off the road, firebombing the vehicle. The presence of a federal marshal on the bus saved the integrationists from death.

Address

Gurnee Avenue, Anniston, AL, United States

The largest and most prominent African American church in Birmingham, 16th Street Baptist Church joined the 1963 civil rights campaign in response to Dr. King’s appeal to its pastor for support. As Shuttlesworth and Dr. King led the April 1963 protests to challenge racial segregation in most of its manifestations, demonstrators gathered here adjacent to the “colored” Kelly Ingram Park as police attempted to keep them in the Black section of town. When the Children’s Crusade began in May 1963, youth gathered at 16th Street before departing through the park headed toward downtown. Authorities used blasts of water from fire hoses and police dogs to break up the demonstrations. The violent suppression of nonviolent Black youth convinced the Kennedy administration to propose civil rights legislation. Trying to stop school desegregation that fall, Ku Klux Klansmen dynamited the church, killing four Black girls.

Address

1530 6th Avenue North, Birmingham, AL, United States

As Mississippi’s NAACP field secretary and civil rights attorney, Medgar Evers assisted most of the protests in the state, from the student sit-ins at the Jackson Woolworth’s to the Freedom Rides. He joined with others in forming the Council of Federated Organizations to promote freedom schools and voter registration. On June 12, 1963, Evers conducted a mass meeting in Jackson to listen to President John F. Kennedy in a nationwide broadcast call for civil rights legislation. Upon returning home, Evers stepped out of his car only to be assassinated in his driveway.

Address

2332 Margaret W Alexander Dr, Jackson, MS, United States

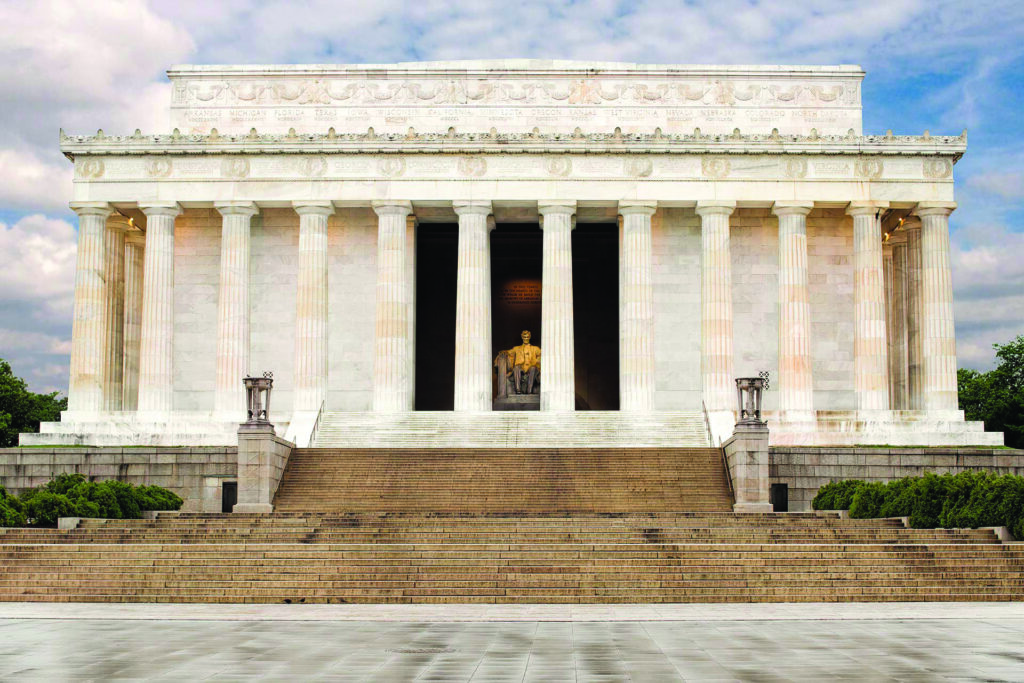

Planned by longtime civil rights activists A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin of the March on Washington Movement, the 1963 demonstration pressed for passage of President John F. Kennedy’s civil rights legislation along with the economic reforms originally proposed in the 1941 march. Having studied satyagraha in India and being a founding member of the Congress of Racial Equality, Rustin trained movement leaders and volunteers in nonviolence. On August 28, 1963, with millions watching on television, 250,000 people peacefully gathered on the National Mall in front of the Lincoln Memorial to hear civil rights speeches, the most famous of which was Dr. King’s “I Have A Dream.” Five years later, the adjacent area housed Resurrection City as the Poor People’s Campaign occupied Washington.

Address

2 Lincoln Memorial Circle Northwest, Washington, DC, United States

With the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ending the legal white supremacy of racial segregation in public accommodations, activists turned their attention to voting rights as a way to gain Black political empowerment and secure and advance their interests. Since the Freedom Rides, civil rights activists had mobilized Black communities in rural areas where they were a majority behind voter registration drives in Southwest Georgia and Mississippi, culminating in Alabama. Yet white supremacists controlled local governments and resisted their efforts. Months of protests over access to courthouses and the franchise led to the call for a Selma-to-Montgomery march to demand the vote from Alabama’s governor. On March 7, 1965, nonviolent activists crossed over the Edmund Pettus Bridge only to confront sheriff deputies and state patrolmen, who brutally beat the activists. As the federal courts authorized the march to continue, President Lyndon B. Johnson pushed through Congress the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Address

Edmund Pettus Bridge, Selma, AL, United States

After joining a movement in Chicago over slum housing in 1966 that failed to result in reforms, Dr. King spoke out in 1967 against the U.S. war in Vietnam as he emphasized the “triple evils” of racism, militarism and poverty. With the SCLC, he prepared a Poor People’s Campaign to occupy the federal government and demand economic justice. In Memphis, Dr. King’s colleague James Lawson had joined the leadership of striking sanitation workers and encouraged Dr. King that their protest reinforced the objectives of the Poor People’s Campaign. Dr. King led a Memphis march with the strikers, but agent provocateurs provoked violence, discrediting the movement. Determined to show the efficacy of nonviolent protest, Dr. King returned to Memphis and delivered his “Mountaintop” speech. The next evening an assassin shot him as he stood on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. Days later his widow, Coretta Scott King, and their children led a nonviolent procession of 25,000 people silently through Memphis streets as the city negotiated an end to the strike. Weeks later the U. S. Congress passed the 1968 Civil Rights Act, which called for fair housing.

Address

450 Mulberry Street, Memphis, TN, United States

The legacy of slavery in the U.S. left a system of legal white supremacy, resisted by African Americans striving for freedom. Post-Civil War, attempts were made to enforce racial equality through federal laws and constitutional amendments. However, widespread hostility ended these efforts, leading to the “Jim Crow” laws in the South, which enforced segregation under the guise of “separate but equal.”

The Modern Civil Rights Movement began with protests against school segregation. Notable actions included Barbara Johns’ student walkout in Virginia and the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case, which declared segregated schools unconstitutional. Resistance from the South led to federal intervention, such as President Eisenhower sending troops to protect the Little Rock Nine.

Rosa Parks’ arrest sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott, led by Martin Luther King Jr., which expanded the fight against segregation in public accommodations. The movement saw further action with sit-ins, Freedom Rides, and significant events like the March on Washington and the Selma to Montgomery March.

These efforts culminated in major civil rights legislation, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. The movement also highlighted economic inequalities, leading to campaigns like the Poor People’s Campaign. Despite King’s assassination, the movement’s legacy persists in the ongoing struggle for equality and justice.

Georgia State University World Heritage Initiative